Which lenses fit my camera?

Want to invest in a lens for your camera, but don’t know where to start? First up, you’ll need to know which lenses are compatible with your camera.

You can get quite a bit wrong when you buy a lens. At least these mistakes mean you’re gaining experience and, over time, help you understand what you need. But there’s one mistake that doesn’t come with experience: when your newly purchased lens doesn’t actually fit your camera. This guide is aimed at preventing bad buys.

The bayonet

Your camera is part of a certain system, that’s why cameras with interchangeable lenses are called system cameras. Each system comes with its own bayonet – the term used to refer to the fastening mechanism between your camera and the lens. If both parts have the same bayonet, you can screw on the lens. If not, you either won’t be able to do this or will only be able to do so with the help of an adapter. I’ll get to those later.

But when do cameras and lenses use the same bayonet? This tends to be the case if they’re produced by the same manufacturer. However, this is by no means a sure indication. Some manufacturers produce multiple systems that are incompatible with each other. Conversely, there are also manufacturers who use the same mechanism. But one thing’s certain. Lenses by Canon, Fujifilm, Nikon, Pentax and Sony are only compatible with cameras of their own brand.

Source: David Lee

Third-party manufacturers including Sigma, Tamron or Tokina produce lenses to cater for different systems. Again, you need to know which model will fit your camera.

Ultimately, there’s only one method that’s airtight. You need to know the designation for your lens mount. In most cases, it’s already part of the name of the lens. Often, the cameras also have the designation in their name. You can find a table with all designations below. But first, a word about the sensor size, as this is a trap beginners often fall into.

Sensor size: beware of the narrow field of view

If your lens screws onto your camera, that’s a good sign. However, it doesn’t mean that everything’s perfect. Why? Because each lens is made for a certain sensor size. If the sensor size of your camera differs from this, you can still take photos with the lens, but the image will be cropped.

If you don’t know the sensor size of your camera, search the web for the name of the camera together with the term «sensor size». The table below gives you more hints on how to check. The following sizes are common:

- Micro Four Thirds: 17 × 13 mm

- APS-C: approx. 24 × 18 mm

- 35 mm format (also called full-frame format): approx. 36 × 24 mm

- medium format: digital 44 × 33 mm

Micro Four Thirds and medium format each comprise only one sensor size. Therefore, the camera sensor and lens definitely match.

This is different with APS-C and 35 mm because Canon, Nikon, Pentax and Sony use these two sensor sizes with the same bayonet.

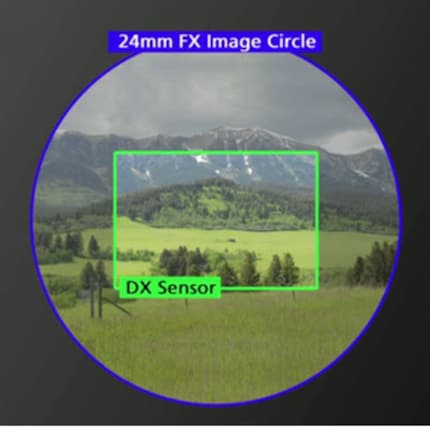

In these cases, you can attach a 35 mm format lens to an APS-C camera. The field of view is smaller than with a 35 mm camera because the sensor is smaller. As long as you’re aware of this, it’s not a problem.

Source: Nikon

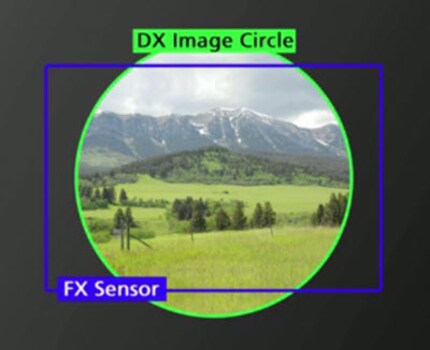

Inversely, this also works to connect an APS-C lens to a 35 mm camera.

This creates black edges around the photos because the lens doesn’t expose the entire sensor. Frequently, the image is automatically cropped to APS-C size. In other words, not only the field of view is narrowed, but the resolution is reduced, too. So this version makes less sense than putting a 35 lens on an APS-C camera. In fact, Canon has even made this mechanically impossible to do with single-lens reflex cameras. With mirrorless cameras, on the other hand, the combination works.

Source: Nikon

To find out which image section you get if you use the «wrong» lens, you have to multiply the focal length by a factor of 1.5 or 1.6 for Canon. For example, a lens with a focal length of 50 millimetres on an APS-C camera produces the same image detail as a lens with 75 millimetres on a 35 mm camera. With Canon, we’re looking at 80 millimetres.

But caution: if a lens says «50 mm», it will always display the same crop on an APS-C camera – regardless of whether it’s made for APS-C or 35 mm. This is because it’s the camera that narrows the field of view, not the lens. With a 35 mm camera, on the other hand, it’s the lens that narrows it. An APS-C lens of 50 millimetres therefore displays a smaller field of view on the 35 mm camera than a full-frame lens with the same focal length.

The designations

Print it out, stick it on your fridge and memorise it. I’m serious. These terms are really important if you want to navigate the lens jungle.

Here’s an example for you: Nikon has two bayonets. The F bayonet for SLR cameras and the Z bayonet for mirrorless cameras. Both cater for the sensor sizes 35 mm (KB) and APS-C. The lenses for the APS-C format are marked with the abbreviation DX in both systems.

As you can see, Canon is currently the most complicated in this regard. For more info, check out the Canon lens compatibility website (in German) – about halfway down you’ll find a summary table.

The table doesn’t include the designations of third-party manufacturers. They generally produce their lenses for several systems and use their own designations. In those cases, you have no choice but to work your way through the specifications. That’s where you’ll see which bayonet and sensor size work with which lens.

Adapters: your workaround

Incompatibilities can be bridged with an adapter. However, it’s not something I’d recommend for beginners. Adapters are particularly useful if you already have a good lens and want to continue using it on a new camera.

The most common case is SLR lenses for Canon and Nikon cameras, which can be used on other mirrorless cameras with an adapter. These adapters also work for both sensor sizes and without any quality compromises. They merely provide the optically necessary distance between the lens and the sensor. Careful with old Nikon lenses like this, which don’t feature a built-in autofocus motor. They only work manually on a mirrorless camera.

By the way, the reverse is physically impossible. Mirrorless lenses can’t be connected to an SLR camera with an adapter either. This is because the distance between the sensor and the lens would have to be shortened.

Quiz

Test your knowledge on the subject with this quiz.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Practical solutions for everyday problems with technology, household hacks and much more.

Show all