Testing Sony’s X95L: countering OLED with mini-LEDs and Bravia Core

Sony wants to shake up the LCD market with its mini-LED TV – just like Samsung did last year with Neo QLED. But it’s actually Sony’s Bravia Core, a new kind of streaming service, that really gets me excited.

Full disclosure: the TV, a 65-inch version of the X95L, was provided to me by Sony for testing.

Not everything that glitters is OLED. Not with Sony. True, Sony is definitely one of the better OLED TV builders in the industry. Regardless, the X95L isn’t an OLED TV, but a so-called LCD TV with mini-LEDs: thousands of closely spaced LEDs provide the background light for your TV. Unlike OLED pixels, LCD pixels don’t shine by themselves. That’s why the TV game in 2023 will be primarily split between these two technologies.

Right off the bat, the central question: which technology is better? The answer isn’t always obvious. OLED TVs are generally considered superior in contrast, colour fidelity and volume. But in bright living rooms, LCD TVs come up trumps as their tech makes them even more radiant. If you mainly watch TV in the evening, you’re more likely to go for an OLED. If you use it more during the day, when the living room’s bright, an LCD TV is more worthwhile.

To avoid comparing apples with oranges, I’ll primarily contrast Sony’s X95L with the Samsung Neo QLED QN95B in this review – that’s Samsung’s mini-LED TV. You can find the review of that model here. In short, I was thrilled. The bar that Sony’s X95L has to clear in this detailed review is pretty high as a result.

Let’s get stuck in.

Design: a convincingly clever stand system

There it proudly stands, on its two black metal duck feet. It isn’t really my style; I’ve never really liked Sony’s industrial look. But it’s practical. Firstly, the feet aren’t placed centrally, like on most competitors. Secondly, there’s a gap of 8.5 centimetres between the panel and the TV cabinet. This leaves enough room for most large soundbars without them protruding into the picture.

Source: Luca Fontana.

This gap would only be unsightly if you don’t have a soundbar. But Sony has thought of this too. The two duck feet can also be attached to the panel so that the gap is «closed». The feet are then barely visible from the front and back, while the panel sits directly on the TV unit.

Very smart indeed. Looks nice too. If I didn’t have a soundbar, I’d definitely go for this configuration. Here it is in the Zurich digitec store.

Source: Luca Fontana.

Otherwise, Sony stays true to what most other manufacturers imagine a TV to be. Modern. Slim, with narrow edges. Nothing extraordinary – and that’s a good thing. TVs should be TVs, in my opinion.

Viewed from the side, Sony’s X95L is quite thick at 6 centimetres. This is down to the additional LED layer that lights up the LCD pixels in the panel. There you go, mini-LEDs.

Source: Luca Fontana.

Now for the specs. Sony’s X95L offers the following:

- 4× HDMI 4K120Hz 2.1 ports

- One of those with eARC (HDMI 2) and two with ALLM and HDMI Forum VRR (HDMI 3 and 4)

- 2× USB 2.0 ports

- 1× USB port for external HDDs

- 1× Toslink output

- 1× LAN port

- 1× CI+ slot

- Antenna and cable connections

- Bluetooth (BT 5.1)

- Built-in Chromecast

- Compatible with Apple AirPlay 2, Apple HomeKit and Google Home

All four HDMI inputs support HLG, HDR10 and Dolby Vision. Only HDR10+ is missing. That’s a pity. Having said that, it’s not widely available anyway. To date, I’ve only come across HDR10+ content once on Amazon Prime Video. By contrast, the passthrough function of Dolby Atmos and DTS 5.1 audio signals is a really positive aspect. You’ll need this if you’re using an external device as a player. A UHD Blu-ray player, for example. Unfortunately, I couldn’t test whether the passthrough function also works with DTS:X because my soundbar – a Sonos Arc – only supports DTS 5.1 Surround at most.

And a word about weight. Without the foot stand, the TV weighs in at 32.2 kilos. So if you want to mount your TV to the wall, you’ll need a VESA 300 × 300 mm mount. You can find them in the shop here. With the two stands, the TV weighs 33.7 kilogrammes.

Measurements: good, but no top values for Sony’s X95L

The following is a deep dive into the subject matter. If you’re not into charts and diagrams, just skip it all and scroll straight to the section «The picture: mini-LED worthy material with the usual strong processor». From that point onwards, you can expect a lot of my subjective impressions and quite a bit of video material.

I measured all the TV’s screen modes with professional tools from «Portrait Displays». I took a closer look at «Standard», «Cinema» and «Dolby Vision» without calibrating or manually changing the settings. Basically, how most mere mortals would use a television. After all, you want to know if a TV’s precise and true to colour even without expensive, professional calibration.

Cinema mode achieved the best scores. However, since almost all streaming services automatically switch to Dolby Vision for HDR content, the measurements below refer to the TV’s Dolby Vision Bright mode.

Maximum brightness

Mini-LED technology isn’t entirely new. However, it was vital for LCD TVs to survive in 2020, when Chinese TV manufacturer TCL launched the novel, small LEDs for the first time. This is down to the way LCD televisions work: where pixels are supposed to remain black, the LED light is blocked off by light crystals and polarisation filters. At least that’s how the theory goes. But in practice, a little light always penetrates. Which is why LCD televisions tend to be dark grey where there should only be darkness.

That’s why TV manufacturers have come up with mini-LEDs: thousands of microscopic LEDs that dim locally. This ensures better black levels – and thus better contrasts that supposedly rival the OLED competition. The following applies: the more LEDs are grouped into dimmable zones, the more efficiently annoying blooming can be reduced. Blooming is a kind of halo that occurs when bright edges against a dark background aren’t illuminated with pinpoint accuracy. Pay attention to the shirt in the comparison from the show Westworld below. Or the dark area to the left of the woman’s face. On LG’s 2020 8K TV, it looks like they’re shimmering.

Source: UHD Blu-ray, Westworld, Season 2, Episode 2. Timestamp: 00:11:50.

Right, let’s take a look at the brightness of the X95L. In the chart, I compare directly with Samsung’s QN95B, the mini-LED competitor, and LG’s G3, currently the best and, according to my measurements, the brightest OLED TV in the world. There are two axes: the vertical one stands for brightness, the horizontal one for the section in which the brightness is measured.

Huh? Sony’s X95L results in an outcome that I’ve never seen before in my measurements:

Nit is the English unit of measurement for candela per square metre (cd/m²), i.e. the luminance or brightness. One hundred nits corresponds approximately to the brightness of a full moon in the sky at night. Visuals: Luca Fontana/Flourish.

First, it achieves a total value of only 1,283 nits across two per cent of the entire screen area, low by LCD standards. Second – and this is the real surprise – the TV initially gets brighter as the image section gets larger, before the brightness decreases again. Normally, brightness decreases in proportion to the increasing image detail. Otherwise, the brightness would burn the eyes out of your skull. But the X95L only reaches its peak value at 25 per cent of the total screen area: 1,583 nits.

What does this tell us? For one, the 1,413-nit brightness that LG’s G3 initially achieves is an awesome result. Especially for an OLED TV. In contrast, Sony’s X95L is definitely weaker. Samsung’s QN95A achieves an incredible 2,104 nits. I’d have expected Sony to be somewhere close. If a TV shines brightly at specific points and in very small sections, this usually results in better contrast and more colours. OLED TVs don’t shine as brightly as LCD TVs, but still score more in contrast ratings. This is because they’re vastly superior to LCD TVs on the other side of the spectrum – black level.

The X95L doesn’t score well in either brightness or black level. Spoiler: this is exactly what will affect later measurements.

Source: Luca Fontana

Sony’s X95L is quite decent in terms of brightness in the 100 per cent window – that is, an area as large as the entire display. There, the X95L comes in with 648 nits. This is almost as bright as Samsung’s QN95B. LG’s G3, on the other hand, «only» has 250 nits, still a very good value for OLED TVs.

Why do I emphasise this? Because it’s the brightness at 100 per cent of the window size that first allows conclusions to be drawn about the real overall brightness of the TV, not peak brightness values beyond the 2,000-nit mark used in the manufacturers’ marketing. Or in other words: Sony’s X95L and Samsung’s QN95B are about equally bright, but Samsung’s TV should have advantages in contrast and colour space coverage thanks to its better peak brightness.

We’ll get to that.

The white balance

Let’s take a look at the white balance of the TV. You get white on a TV when the red, green and blue subpixels of each pixel radiate simultaneously and with equal intensity. In other words, full brightness generates the brightest white. The lowest brightness, on the other hand, creates the deepest black. If the subpixels can be switched off completely, as is the case with OLED or QD OLED, this is referred to as true black. Therefore, everything in between is nothing more than shades of grey.

To measure the accuracy of the white balance, I need two tables:

- Greyscale delta E (dE)

- RGB balance

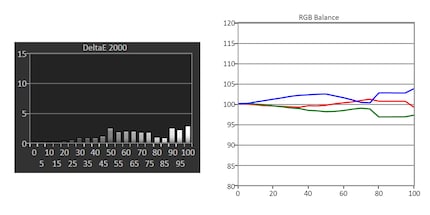

The greyscale dE shows how much the greyscale generated by the TV deviates from the reference value. The RGB balance indicates in which direction the greyscale levels produced by the TV deviate from the reference value. Why is this important? Let’s take a look at the concrete X95L example:

Source: Luca Fontana

If you were to put the TV right next to a reference monitor, that would mean:

- Value is 5 or higher: most people will see the difference to the reference monitor.

- Value between 3 and 5: only experts and enthusiasts will be able to tell the difference.

- Value between 1 and 3: only experts will see the difference, enthusiasts won’t.

- Value below 1: even experts will not see any difference.

Any value lower than five is a very good value for a non-calibrated TV. The average dE for the X95L is at a solid 3.38 dE (dE Avg). This isn’t the best value I’ve measured so far. That one belongs to Samsung’s S95C, a QD OLED TV that I tested here, with an average dE of 1.77. But if you don’t bother with TV measurements and calibrations every day, you’ll hardly see the difference. Good marks for Sony.

A look at the RGB balance (in the top right image) now shows how the white balance deviates from the reference value. This is because a slight blue and green tint stands out wherever the brightest white is located. In other words, the blue and green subpixels shine a bit too strong. But as already mentioned, the deviation is only around dE 5. In other words, it’s highly unlikely that you’ll actually perceive a blue or green tint as such in a real image.

The colour gamut

Now for measuring the colour gamut; the coverage of the most common colour spaces. These are:

- Rec. 709: 16.7 million colours, standard colour space for SDR content like live TV and Blu-rays

- DCI-P3 uv: 1.07 billion colours, standard colour space for HDR content, from HDR10 to Dolby Vision

- Rec. 2020 / BT.2020 uv: 69 billion colours, still barely used in the movie and TV industries

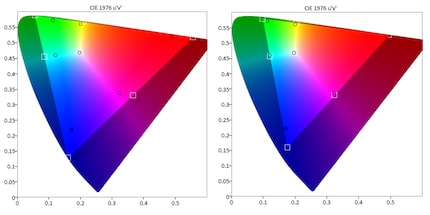

Source: Luca Fontana

The large blob of colour, including the darkened areas, shows the full range of colours detectable by the human eye. The lightened area on the left shows the BT.2020 colour space. On the right, you’re seeing the same, only the smaller DCI-P3 colour space. The white boxes show the actual boundaries of the respective colour spaces. The black circles, on the other hand, represent the limits actually identified during the measurement.

The measurement showed the following colour space coverage:

- Rec. 709: 100% (good = 100%)

- DCI-P3 uv: 89.35% (good = >90%)

- Rec. 2020 / BT.2020 uv: 63.48% (good = >90%)

Remember what I said above about the relationship between peak brightness and colour space coverage? Exactly this can be seen here: the X95L achieves only 89.35 per cent coverage in the important DCI-P3 colour space. Samsung’s QN95B achieved 92.49 per cent coverage in the same test – and thus more than the target 90 per cent that a good TV should have.

For comparison: Sony’s and Samsung’s QD OLED TVs as well as LG’s OLED TVs all come to around 99 per cent coverage in this test.

Now for the BT.2020 colour space. Sony’s X95L covers this with «only» 68.48 per cent. Admittedly, currently only Sony’s and Samsung’s QD OLED TVs achieve a value of slightly over 90 per cent. It’s exactly why the BT.2020 colour space is still hardly used in the industry (see info box above). But even Samsung’s mini-LED TV still manages 71.27 per cent coverage. I’d have thought Sony’s mini-LED TV could manage more here.

The colour error

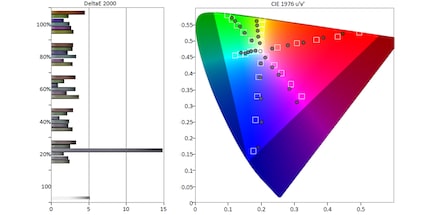

Now for the colour error. What it does is describe how accurately colours are represented. As with greyscale above, the deviation from the TV to the reference value is referred to as dE. The white boxes indicate the reference colours sent to the TV by the test pattern generator. The black circles, on the other hand, represent the colours actually measured. Again, dE values below 5 are good for non-calibrated TVs.

Source: Luca Fontana

Here, too, I’m somewhat disappointed – although things are generally much better. The measurements show an inherently good colour fidelity in Dolby Vision Bright mode. But one that «only» achieves an average dE of 5.79 with a total of 40 measured values. This is only marginally above the target value of 5. In the end, it’s still above. It’s why I said things were much better. Samsung’s QN95B scored a very solid 2.97 in this test.

Reflections

You can’t measure reflections on your screen as such. But some of you requested I take a look at it in my tests. Good idea. For testing, I recreated a standard situation in a living room: first, an evening photo. There’s an oven behind me and a standard lamp next to the TV. The light from the standard lamp is reflected in the glass door of the oven behind me and thrown back onto the TV.

Here’s the result:

When testing Samsung’s mini-LED TV, I hadn’t used the mirroring test yet. Therefore, you can see the comparison with LG’s G3 here, which is visibly better with reflections. Much better. Again, the X95L disappoints me.

But reflections are much more glaring during the day, without closed curtains, blinds or shutters, when light also hits the panel from the side. I mean, look at this:

Source: Luca Fontana

Fortunately, Sony’s X95L shines bright, as is typical for LCDs. Annoying reflections are rarely noticed during the day. At least not in bright scenes. In dark scenes, however, the reflections were annoying from time to time.

Interim verdict after measuring

The measurements speak loud and clear: Sony’s X95L certainly isn’t a bad mini-LED TV. But it doesn’t achieve top values: the moderate peak brightness unfortunately has a visibly negative effect on colour space coverage. True, the colour fidelity is good, but not outstanding. And I always struggle with reflections, especially during the day, in dark scenes. Let’s see what the practical test has to say about it.

The picture: mini-LED worthy material with the usual strong processor

That’s the theory done with. But how are things in practice? Reminder: to avoid comparing apples with oranges, I’ll primarily contrast Sony’s X95L with the Samsung Neo QLED QN95B in this review – that’s Samsung’s mini-LED TV from last year.

Colour rendering

Whenever I test a TV for its colour reproduction, I go for Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2. Especially this scene: Ego’s golden palace popping in the saturated evening red. Drax’s greenish skin full of blood-red tattoos in the midst of it. Compared with Samsung’s Neo QLED, I especially notice that the Samsung’s dark tones are a bit deeper. This makes the picture look like it has more punch to me – a bit like OLED TVs. Sony’s picture looks a bit more natural because the warmth of the evening light is less glaring.

To provide some variety, I’ve included a scene from Avatar: The Way of Water, starting at minute 00:22, where green and especially blue tones dominate. As the movie only hit theatres after my Neo-QLED review, I’m comparing it to my current favourite, LG’s G3 OLED TV, just this once. Especially with the bluish skin tone of the nature-loving Na’vi, I quickly notice that LG’s TV has a much better colour fidelity. Unsurprisingly, the black levels are also better – after all, this is the OLED TV’s main strength.

Source: Disney+, Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2». Timestamp: 00:56:47.

Let’s circle back a bit. I want to see what colours look like outside of computer-generated worlds. Take James Bond – Skyfall. James and young quartermaster Q are at an art museum, looking at a painting of a proud old battleship being unceremoniously towed to the scrapyard. The scene is obviously an allusion to the ageing secret agent.

Here, Sony’s picture already convinces me more. Pay special attention to the natural skin tones. A slight red tone creeps into the Samsung picture. I already criticised this in the Neo-QLED review. Otherwise, however, both TVs are operating at a very high level.

Source: Apple TV+, James Bond – Skyfall. Timestamp: 00:39:02.

Black crush and shadow details

How does the latest Sony mini-LED perform in dark scenes? For this test, the first scene from Blade Runner 2049 comes into play. But first, Sony’s X95L seemed to shine particularly bright with an orange background. There’s no other way I can explain why my camera delivers such an overblown image. I always fix the aperture in place so that the test video doesn’t flicker. Therefore, ignore those few seconds on the Sony TV.

The rest of the clip says more: just around the window, you can see how Sony’s additional dimming zones provide visibly less blooming than Samsung (above, in the section «Maximum brightness», you can find out what I’m talking about here). In addition, there’s a very deep black, especially for an LCD TV. However, the second (unfair) comparison with LG’s G3 OLED TV starting at minute 00:50 shows that it can be even better.

Source: UHD Blu-ray, Blade Runner 2049. Timestamp: 00:04:50.

Brightness gradations

And here’s for a final image test: brightness gradations. I want to see how well Sony’s X95L renders bright areas of the image in particular. Again, I notice that Sony obviously puts more power into the LEDs in bright image areas than Samsung. Pay attention to the sun, which is barely visible on the Japanese TV and also «swallows» the clouds around it. It seems Samsung controls its LEDs in a more balanced way, especially in terms of brightness.

Source: UHD Blu-ray, Jurassic World. Timestamp: 00:21:18. Side note: the brief judder in the Samsung S95B video stems from my overheated camera. It had had enough after a long, hot summer day.

Processor: the usual strong level

The processor is the TV’s brain. Its main task is to receive, process and then display image signals. In this context, processing means recognising poor image quality and enhancing it. It does this by removing noise, enhancing colours, smoothening edges, making movements more fluid and adding any missing pixel information.

Motion processing and judder

For this test, I want to make the processor sweat. Concretely, by taking a look at judder. Something all TVs are affected by. Especially with long camera pans. Sam Mendes’ 1917 is full of such steady, slow-flowing camera movements, making it perfect for the judder test. In my comparison with models by other manufacturers, I pay particular attention to the vertical beams in the barn, checking whether they run smoothly through the image or judder.

Source: UHD Blu-ray, 1917. Timestamp: 00:42:25.

Don’t be alarmed: Sony’s picture never stutters as much as here in most scenes. But yes; if you don’t change anything in the settings yourself, it’ll stay like this. By the way, this is typical for Sony: by nature, the Japanese manufacturer is reluctant to engage in judder reduction. In Sony’s eyes, movies have to be a bit jerky – like they were at the cinema before the digital age. Nice and old-fashioned. For me, it’s too much. Even if I adjust the Clarity settings, the judder doesn’t disappear completely. In addition, other «normal» scenes suddenly look like soap operas. With Sony, I’ve basically always had trouble finding a balance I enjoy in this regard. Other manufacturers do it better.

Let’s skip to the next scene from 1917. Again, Mendes’ camerawork constitutes an immense challenge for most processors. Especially hard edges in front of a blurred background – take the helmets of the two soldiers below whenever they cross in front of branches and shrubbery. Both the processor and pixels have to react incredibly fast.

Source: UHD Blu-ray, 1917. Timestamp: 00:35:36.

Sony’s processor doesn’t show any weakness in this discipline. Only the judder is – as always – a bit visible as long as you’re making a direct comparison.

Pixel response time

Next up, the Apple original For All Mankind. I want to see how long a single pixel takes to change colour. You can tell if the pixels aren’t changing colour fast enough when the image looks smeared – an effect known as «ghosting». When the camera pans over the surface of the moon, pay attention to the superimposed text.

Source: Apple TV+, For All Mankind, Season 1, Episode 5. Timestamp: 00:00:10.

Problems? Not at all. At least not with Sony and Samsung, where superimposed texts always stay sharp. But just so you can see what the smearing I’m talking about looks like, I’ve included a comparison with TCL’s mini-LED in the video above too. In the spirit of fairness, I do want to emphasise that this comparison is with the C82 model, which is over two years older than Sony’s X95L. The example is only meant as an illustration. TCL’s successor model, the C92, released last year, is a clear step up in this regard.

Upscaling

Now for one of the most difficult tests: upscaling. I want to see how well the processor upscales lower quality material. For example, Blu-rays or good old live television shows. Or The Walking Dead. The series was deliberately shot on 16 mm film to preserve the old-fashioned grain that creates the feeling of a broken, post-apocalyptic world.

Source: Netflix, The Walking Dead, Season 7, Episode 1. Timestamp: 00:02:30.

Before you ask, yes, I did indeed compare two different clips. Samsung’s image has a barely visible red cast if you look closely. Otherwise, Sony’s processor again cuts a good figure here. I say again because Sony’s processors have proved particularly good at upgrading inferior sources over the years. Basically, the picture is sharp, pleasantly warm and rich, but still natural. And there’s barely any image noise or compression artefacts. Sony’s QD OLED TV had a lot more trouble last year, as you can see here.

Gaming: input lag and game mode

When measuring the colour accuracy in Game Mode, I get a splendid average Delta E of 3.01 (read the section on colour error further up if you’re interested and want to learn more). This is no reference image level, to be sure. But it’s one of the best values I’ve ever measured for a TV in Game Mode.

On to input lag. Using the measuring device from Leo Bodnar, I measured an average input lag of 18.9 milliseconds for a UHD picture at 60 frames per second. Not exactly overwhelming. But within the 20 milliseconds allowed for TVs, which any Game Mode should manage in 2023. In addition, the TV supports all features relevant for gamers:

- 4x HDMI 2.1 ports (4K120Hz)

- Auto Low-Latency Mode (ALLM)

- Variable frame rates (HDMI Forum VRR)

Sony – like Samsung, LG, Philips, TLC and Panasonic – has also entered into a partnership with many large gaming studios. As part of the HGIG, or HDR gaming interest group. According to the manufacturer, this should ensure that HDR is displayed as the game developers intended – like when playing Spider-Man: Miles Morales on the PlayStation 5.

Source: PS5, Spider-Man: Miles Morales, 120 Hz mode, VRR and ray tracing enabled.

What Sony conjures up here is a picture with absolutely perfect colours. In addition, I notice that black is really black, the edges look sharp and the image stays sharp even during fast and jerky camera pans. Look out for Miles’ dark silhouette against the light, the detailed textures of a snow-covered New York and the extreme detail in the clouds during fights. This is what a good game mode looks like.

Just a shame it doesn’t always feel as good. For example, when playing FIFA23, I failed many a dribble or perfectly timed shot because my inputs weren’t processed and displayed by the TV as quickly as I’m used to on other TVs. LG’s G3, for example, has an input lag of only 10.1 milliseconds.

Smart OS: Google TV

Sony relies on Google TV, which was completely revamped two years ago – much to my delight. Formerly scorned, I now actually consider Google TV one of the most comprehensive yet well laid out operating systems in the TV game. And because Sony’s X95L has a very good processor, Google TV controls smoothly and without noticeable stutters. An all-around successful smart TV package.

Source: Sony Google TV

Unfortunately, an unspeakable fashion in newer operating systems is also back: annoying and never accurate movie and show recommendations. I mean, why is Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire being recommended to me, of all things? The film isn’t new or topical for any reason. And why did these recommendations never change during my entire testing period? No idea. My opinion hasn’t changed: Google (Android TV and Google TV), Samsung (Tizen OS) and the like, if you can’t get the recommendations right, don’t bother with them. Thank you.

A little treat: Sony itself has added a kind of art mode. Instead of turning off the TV, you can display some nice pictures with the date and time. This is meant to liven up the rectangular black hole that a TV otherwise is when off, at low power and low brightness.

Bonus round: BRAVIA Core’s insane!

There you have it: Bravia Core, Sony’s own streaming service, is developing. Slowly. But in the right direction. Two years ago, when testing Sony’s A90J, I primarily raved about it from a technical standpoint. Because Bravia Core isn’t like other streaming services from Netflix, Amazon or Disney. Bravia Core only runs on Sony TVs – but transfers data at a whopping 80 megabits per second.

80 megabits per second!

Here’s the thing about streaming: all content is highly compressed. This is due to the often limited data rates between your TV and the server where the streaming content resides. A data rate of a stable 20-30 megabits per second (Mbps) is required to play UHD HDR content without too much visible quality loss. Netflix and the like can just about manage that – as long as you have an appropriate signal at home. And even then, there may be clearly visible compression losses. In the following example, pay particular attention to the space between the two men.

So, now Sony comes along, manages 80 Mbit/s with Bravia Core and Netflix and the rest are left to stare dumbly on. Sony calls it Pure Stream. Admittedly, with my gigabit connection, I usually «only» get about 55 to 60 Mbit/s when streaming from Bravia Core. Still, that’s a whole lot. Especially compared to other streaming services. Because where the processor isn’t busy with overly demanding decompression, it can use its resources to actually make the image significantly prettier.

This is also reflected in the fabulous picture quality, which can even easily compete with that of UHD Bluray, sporting a data rate between 108 and 128 Mbit/s. Also because Bravia Core adds that most movies are stored with IMAX Enhanced metadata. That’s important. It’s the only way the TV can get the most out of IMAX Enhanced picture mode.

As an example, I’ll show you a comparison between Blade Runner 2049 via Bravia Core and Blade Runner 2049 on my UHD Bluray.

IMAX Enhanced wins, in my opinion. Blacks are even richer than on UHD Blu-ray, and colours are a bit more vibrant without seeming artificially bright. I don’t spot annoying artefacts, picture noise in dark scenes or unsightly streaks on the UHD Blu-ray – as expected – or in the streamed version.

But what’s even available on Bravia Core? Currently only Sony Pictures films, although there’s talk in Japan about bringing other film studios on board. Older Sony films are free. Newer films initially cost one «credit» each, before they also move into the free library after about half a year to a year. When buying a BRAVIA XR TV, you get 25 of these credits for free. Once you’ve used up your credits, you can purchase paid movies within the Bravia app. Payment is made via your Google Play account and the billing method selected there. Price per film: about 10 francs.

Purchasing via credits and the Bravia library looks like this:

Believe me: if this sounds complicated, it was much less clear when I tested it two years ago. At the time, I was still told that Bravia Core itself was only free for two years. After that, additional monthly subscription costs of an as yet unknown amount would be incurred. The Japanese company now seems to have stopped all that – for the time being. What’s also new is that I finally know how paid movies work after the credits are used up. Namely, via Google Play purchases. Two years ago, Sony had no clear plans in this regard.

What’s missing now for Bravia Core to become the ultimate streaming service is primarily content from other movie studios. The challenge, however, lies in the technology: for Pure Stream to work, content must be stored on special Sony servers. This is one big mess, both technically and for licensing reasons, that’s difficult to resolve with other studios, according to Sony executives. But they’re working on it.

Verdict: not the top dog of the mini-LED game – but close

Initially, I said I wanted to compare Sony’s top-of-the-line mini-LED primarily to Samsung’s mini-LED TV from last year. The result: Samsung wins. Sony’s X95L falls behind, especially in terms of brightness and colour fidelity. In the case of the former, by a surprisingly wide margin. Even LG’s G3 OLED TV manages a better peak brightness – tech-wise, a right hook from LG that must have landed hard with Sony.

Outside of the direct comparison, however, Sony shows why the Japanese company is still one of the best TV manufacturers. The picture sports great colour reproduction, always looks natural and is supported by the usual excellent if for my taste much too restrained Sony processor. Even in tandem with a Sony PlayStation 5, the X95L doesn’t show any weakness.

In addition, there’s the ace up the sleeve that other manufacturers don’t have: Bravia Core. This makes even movies that I previously found to be less exhilarating than UHD Blu-ray competition look like complete remasters. This is down to Pure Stream and the IMAX Enhanced metadata. A gamechanger in the streaming world. If only Sony could get other film studios involved as well…

Header image: Luca Fontana

I write about technology as if it were cinema, and about films as if they were real life. Between bits and blockbusters, I’m after stories that move people, not just generate clicks. And yes – sometimes I listen to film scores louder than I probably should.