Background information

Be like Daniel Gyro Gearloose for once: When children become inventive

by Michael Restin

Dyson is researching the future from the depths of the English countryside. The campus is completely sealed off from the outside world, but we were granted a rare glimpse.

James Dyson is ever-present at the Malmesbury campus, the company’s research and development department. The walls are adorned with the founder’s motivational sayings, and there are historical collectibles everywhere to spark inspiration. An ejector seat. A jet gearbox. There’s even a jet – an English Electric Lightning – hanging over our heads in the cafeteria. And by us I mean a group of media professionals from all over Europe whom Dyson had invited to visit the two research centres in Malmesbury and Hullavington.

If you didn’t already know that Dyson primarily develops vacuum cleaners and hair dryers, you’d guess it was Q’s secret research institute from James Bond. That’s also what the safety measures would have you think. Revolving doors seal off the area, and you can only access offices and labs with a badge. High security in the middle of nowhere. Malmesbury is a village of 5,000, tucked away in the rolling countryside of south-west England. The nearest city is Bristol, 50 km away, while London is a 150-km-trip.

On site, engineers are busy developing the future of the Dyson brand. Students can even gain their bachelor’s or master’s degree at the company’s own university, the Dyson Institute. Most live on campus for the first few semesters in utilitarian rooms that look like cardboard boxes stacked wildly on top of each other. They spend their study, work and free time on campus.

We meet engineer Josh Mutlow in a barren boardroom next to an open-plan office. When Josh joined Dyson in 2011 straight out of uni, the institute didn’t even exist. Josh worked his way up from Design Engineer to Senior Design Manager in his 12 years and has high praise for the Dyson system: «Hardly any companies give graduates so much responsibility and freedom». Brimming with enthusiasm, he explains how projects work at Dyson and how closely the various departments collaborate. How quickly they can realise designs thanks to cutting-edge 3D printing technology. And what James Dyson requires of them when they meet to review a project’s progress.

«James and his son Jake challenge and motivate us daily.» Others would call it micromanagement, but here it’s seen as inspiring. Working at Dyson is like being part of a cult, with guru James at the top and disciples who blindly follow him.

«That’s not at all the case. We’re meant to take our own creative approaches. Thinking outside the box, and even failing sometimes,» explains Josh. He says it’s about solving problems in creative and effective ways. For instance, how to get a robot vacuum cleaner to do the most effective job along a wall. Or deciding whether the robot’s eyes should be a camera or a laser scanner. «Solutions to problems» has to be the saying that was repeated most often, almost like a mantra, when we visited Malmesbury.

We do also get some answers. The problem with the wall vacuum, for instance, has been solved with a strip of silicone that folds out on the side of the robot, redirecting suction to the wall. In terms of the laser scanner or camera question, the engineers at Dyson opt for a camera. They see these as the future due to their ability to process much more data. Obviously without saving the data or uploading it to the cloud. This is also repeated mantra-like.

And what does the future hold? «Are we allowed to talk about that?» an engineer asks the Dyson PR managers, who are giving us a tour of the Malmesbury campus. They shake their head in response. A hint that we’ll get to see plans for the future the following day in Hullavington. That’s where Dyson’s second campus is located, just round the corner on an old military airfield. Robotics and AI are the big research topics here – and the subject of my next article.

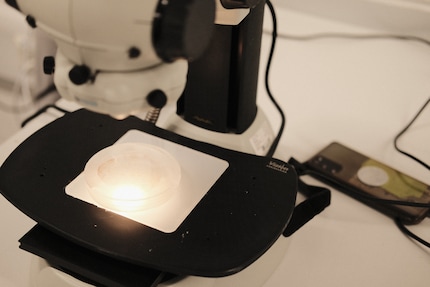

What you can and can’t do at Dyson is a bit tricky. As a general rule, taking photos on campus isn’t allowed. Apart from test scenarios, which have been set up specifically for the journalists. We enter a large hall where they’ve built the laboratories. From the bio lab in the office container to the huge, walk-in metal cube for measuring radiation: everything can be thoroughly tested here. How loud is a vacuum cleaner motor? How much radiation does the power supply emit? What’s the suction and blowing quality like on the devices? How efficiently do fans circulate air in a room? We even get to see a colony of house mites, magnified through a microscope.

Engineers give us an insight into their typical working day via short demos. They measure, evaluate and test according to international standards. «That’s the secret behind our innovation,» explains a PR manager. «We’re one step ahead of the competition because we can solve problems faster thanks to our laboratories.» Such as the lab that tests the suction power of Dyson vacuum cleaners. In one corner, there are rugs hanging in narrow strips. Flokati, short pile, sisal and Persian rugs can all be clamped into an oblong device and vacuumed automatically. The rugs are strictly standardised. «Only wool from a very special farm in Scotland is used for the short pile, which is EU standard,» explains the PR manager. The cost sits at over 1,000 francs per rug.

The lab’s pièce de résistance is a cupboard with all kinds of dirt in containers, such as baking powder, broken glass, cornflakes and cat litter. All sorted by type and country of origin. Some of the dirt makes two appearances. Cheerios breakfast cereal in the US, for instance, is larger than the version sold in the UK. The dirt is weighed and distributed on strips of rug so that the vacuum cleaner attached to the robot arm can suck up as much as possible. This is all a bit more professional than our test set-up for reviewing vacuum cleaners.

«In our labs, we can replicate the tests for almost all international certificates,» explains one of the laboratory staff. In the past, prototypes and new devices were sent to external laboratories, which cost a lot of money and took even longer. He went on to say that the data was often delivered weeks later, without any explanation or classification. Thanks to its own laboratories, Dyson can now test much more in-house, saving time.

We’ve reached the car park in front of the laboratory building. The visit to the campus is coming to an end. Outside the gates, dozens of employees wait in the drizzle for the company bus to take them to Bristol.

There’s a smell of jet fuel in the air. In the middle of the car park, I see a cylindrical piece of metal with four men we’re not introduced to standing around it. Next to it are two fire extinguishers. «This is one of the first Rolls-Royce jet engines from 1943,» we’re told. James Dyson spent a lot of money on it at auction and even more repairing it. It wasn’t clear whether the engine could still be made to work, as it kept encountering issues. It starts to hiss and snarl. Two minutes later, the spectre is gone. Our group of journalists wonders whether or not it worked this time. The PR squad, too, apparently. As the applause stops, smoke rises from the engine into the grey English sky.

We finish the day in the cafeteria with an explanation of «Dyson Farms». As well as vacuum cleaners and hair dryers, Dyson also produces strawberries and beef tenderloin in the UK. A sustainability project that also started at the research centre because of James Dyson’s interest in agriculture. There’s a greenhouse heated from a power station’s waste heat. The strawberries taste sweet and juicy, while the beef tenderloin would also be good if it were cooked very well rather than just well done. The French vintage 2006 wine makes up for it. Inspired and satiated, we leave the campus through a revolving door that doesn’t work at first. A PR manager hands over the correctly programmed badge. Problem solved. James Dyson would be proud.

Header image: Dyson

When I flew the family nest over 15 years ago, I suddenly had to cook for myself. But it wasn’t long until this necessity became a virtue. Today, rattling those pots and pans is a fundamental part of my life. I’m a true foodie and devour everything from junk food to star-awarded cuisine. Literally. I eat way too fast.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all